Chen Gang asked Boyu [the son of Confucius], "Has the Master imparted to you some different knowledge?” Boyu replied, "Once he was standing alone as I hurried across the courtyard, and he said to me, ‘Have you studied the Poetry?’ I replied, ‘Not yet,’ and he said, ‘If you don’t study the Poetry, you will have nothing to speak.'"

Analects of Confucius , 16:13, translated by R. Eno, 2015

The very word has an allure about it. "Poetry", a simple Google search reveals, has the implicit meaning of "a quality of beauty and intensity of emotion"; it might also mean "something regarded as comparable to poetry in its beauty". Merriam-Webster concurs; poetry is something remarkable in its "beauty of expression". Nor are Anglophones alone. More than a thousand years ago, the Arab writer Ibn 'Abbād (trained in both prose and verse) wrote:

And Ibn 'Abbād seems to have been right, at least since much more of his verse remains than his prose.

For all this, it's remarkable how vague the dictionary definitions of poetry are. Google is quick to tell us that "poetry" is "literary work in which special intensity is given to the expression of feelings and ideas by the use of distinctive style and rhythm". But what distinctive style and rhythm are these? Merriam-Webster turns out to be no better. "Arranged to create a specific emotional response through meaning, sound, and rhythm"—what meaning, what sound, what rhythm? Why is free verse, which is explicitly about not having fixed rhythm, poetry, while Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall is just a "nursery rhyme"?

We need a more technical definition. The World Atlas of Poetic Traditions uses the one proposed by linguist Nigel Fabb in his 2015 monograph What is Poetry?: Language and Memory in the Poems of the World. It goes like this:

"A poem is a text made of language, divided into sections that are not determined by syntactic or prosodic structure."

Let's see what this means exactly.

Poetry isn't (necessarily) syntactically organized

Sections of poetry are not determined by the syntactic (grammatical) divisions of the text. They might coincide, but a line of poetry is not a coherent syntactic unit.

Let's look at a famous English poem.

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds, and shall find me, unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul.

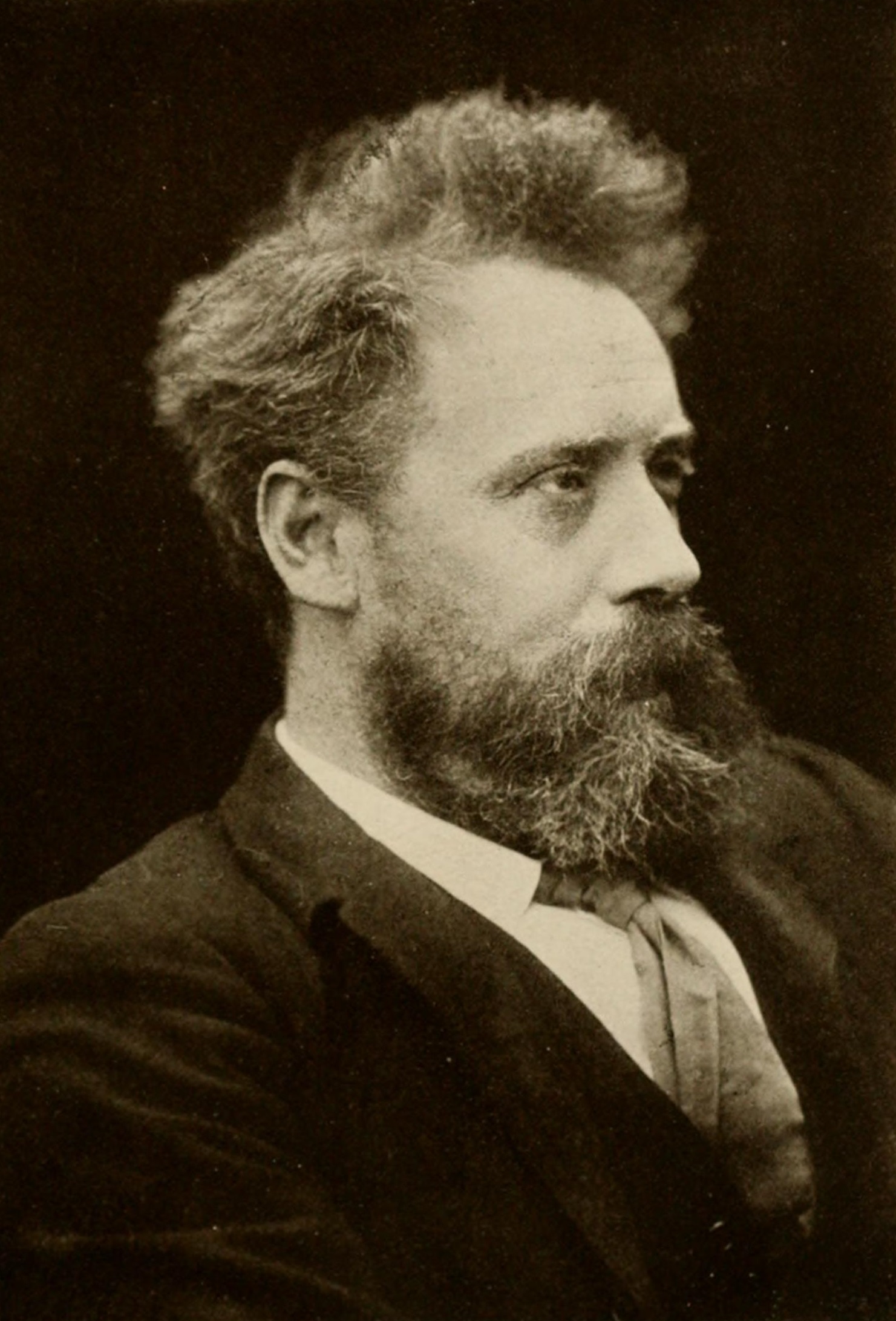

"Invictus", William Ernest Henley, 1875

This poem is divided into sixteen lines (and four stanzas, but we'll ignore them). If this poem was syntactically organized, we'd expect each line to correspond to a consistent grammatical unit: maybe a noun phrase like "the fell clutch of circumstance", maybe a subject or verb phrase, maybe a clause like "I am the master of my soul", maybe even a whole sentence. So let's see:

- Out of the night that covers me : Adverbial phrase

- Black as the pit from pole to pole : Adjectival phrase

- I thank whatever gods may be : Subject, verb phrase

- For my unconquerable soul : Prepositional phrase

- In the fell clutch of circumstance : Prepositional phrase

- I have not winced nor cried aloud : Subject, verb phrase

- Under the bludgeonings of chance : Prepositional phrase

- My head is bloody, but unbowed : Subject, verb phrase

- Beyond this place of wrath and tears : Prepositional phrase

- Looms but the Horror of the shade : Subject, verb phrase

- And yet the menace of the years : Conjunctions, noun phrase

- Finds, and shall find me, unafraid. : Verb phrase

- It matters not how strait the gate : Subject, verb phrase

- How charged with punishments the scroll : Noun phrase

- I am the master of my fate : Clause

- I am the captain of my soul : Clause

Each of Henley's lines, then, must stand for something other than grammatical units.

It's true that in many poetic traditions, subunits of poetry do correspond to coherent syntactic units. In the poems of the Tembagla people of Papua New Guinea, for example, all lines are noun phrases, subordinate clauses, or full sentences. But what's important is that having noun phrases or sentences can't be the defining criteria for Tembagla poetry. After all, every word of Tembagla (like any other language) is organized into one sentence or another, but not every sentence that comes out of their mouths is in verse.

By contrast, in prose (like the prose I'm writing in right now), these chunks of units that exist on top of grammatical ones just aren't there.

Poetry isn't (necessarily) prosodically organized

Sections of poetry are not determined by the prosodic (normally pronounced) divisions of the text. Again, they may coincide, but a line of poetry is not, say, an intonation phrase.

Here's another well-known English poem:

Side by side, their faces blurred,

The earl and countess lie in stone,

Their proper habits vaguely shown

As jointed armour, stiffened pleat,

And that faint hint of the absurd—

The little dogs under their feet.

Such plainness of the pre-baroque

Hardly involves the eye, until

It meets his left-hand gauntlet, still

Clasped empty in the other; and

One sees, with a sharp tender shock,

His hand withdrawn, holding her hand.

They would not think to lie so long.

Such faithfulness in effigy

Was just a detail friends would see:

A sculptor’s sweet commissioned grace

Thrown off in helping to prolong

The Latin names around the base.

They would not guess how early in

Their supine stationary voyage

The air would change to soundless damage,

Turn the old tenantry away;

How soon succeeding eyes begin

To look, not read. Rigidly they

Persisted, linked, through lengths and breadths

Of time. Snow fell, undated. Light

Each summer thronged the glass. A bright

Litter of birdcalls strewed the same

Bone-riddled ground. And up the paths

The endless altered people came,

Washing at their identity.

Now, helpless in the hollow of

An unarmorial age, a trough

Of smoke in slow suspended skeins

Above their scrap of history,

Only an attitude remains:

Time has transfigured them into

Untruth. The stone fidelity

They hardly meant has come to be

Their final blazon, and to prove

Our almost-instinct almost true:

What will survive of us is love.

"An Arudel Tomb", Philip Larkin, c. 1956

The lines and stanzas of this poem are prosodically incoherent. In the sentence that is the second stanza, I've marked the places where I'm inclined to pause when reading out loud:

Such plainness of the pre-baroque hardly involves the eye, // until it meets his left-hand gauntlet, // still clasped empty in the other; // and one sees, with a sharp tender shock, // his hand withdrawn, holding her hand.

But these are Larkin's actual line breaks:

Such plainness of the pre-baroque // hardly involves the eye, until // it meets his left-hand gauntlet, still // clasped empty in the other; and // one sees, with a sharp tender shock, // his hand withdrawn, holding her hand.

Larkin's lines do not correspond to any level of the phonological hierarchy, and yet its beauty is undinted. Again, this is not the case for all poetry in all languages. Traditional Korean poetry is exceptional in that the meter demands that each line contain exactly four accentual phrases, which means that the organization of poetry is prosodically determined. But as with the Tembaglas, not every word Koreans utter is poetry, even though every word they say is organized into accentual phrases. The fact of being organized into accentual phrases alone does not a poem make, Korean or otherwise.

So what exactly are those things that define poetry?

The organization of poetry

Nigel Fabb, whose definition of poetry we're using, argues that all poetry is defined by lines, which are sections of language short enough to fit into "working memory", the short-term memory that lets us process the world around us. These lines, as mentioned, are independent from syntactic chunks of grammar or prosodic chunks of sound. Their existence is demonstrated by a number of poetic devices, principally rhyme, meter, alliteration, and parallelism. (Lines can also be distinguished only in the written form, as is the case in rhythmless "free verse", but these are usually atypical and/or extremely modern works.) We'll look at an example of each of these four, drawing on the two English poems above for meter and rhyme.

Rhyme

Rhymes are probably the single device most consciously associated with poetry by English speakers. In the poetry of English and many other languages, they only occur systematically at the ends of lines and are a very obvious way to distinguish between lines. This is the case with "Invictus", with the ends of each line leading to a rhyme scheme of ABABCDCDEFEFGHGH:

Out of the night that covers me, A

Black as the pit from pole to pole, B

I thank whatever gods may be A

For my unconquerable soul. B

In the fell clutch of circumstance C

I have not winced nor cried aloud. D

Under the bludgeonings of chance C

My head is bloody, but unbowed. D

Beyond this place of wrath and tears E

Looms but the Horror of the shade, F

And yet the menace of the years E

Finds, and shall find me, unafraid. F

It matters not how strait the gate, G

How charged with punishments the scroll, H

I am the master of my fate: G

I am the captain of my soul. H

Here's more proof of how useful rhymes can be in organizing poetry. Take a gander at the following prose translation of the first four lines of Poland's national epic.

Lithuania, my country, thou art like health; how much thou shouldst be prized only he can learn who has lost thee. Today thy beauty in all its splendour I see and describe, for I yearn for thee.

It's impossible to reconstruct how the original Polish lines were divided from this prose translation alone because, again, lines of poetry exist independent of syntax or meaning. Meanwhile, this is the original text:

Litwo! Ojczyzno moja! Ty jesteś jak zdrowie. Ile cię trzeba cenić, ten tylko się dowie, kto cię stracił. Dziś piękność twą w całej ozdobie widzę i opisuję, bo tęsknię po tobie.

The rhymes allow even me, a high schooler who does not speak a word of Polish, to reproduce the four lines correctly (accompanied by the latest verse translation):

Litwo! Ojczyzno moja! Ty jesteś jak zdrowie.

Ile cię trzeba cenić, ten tylko się dowie,

Kto cię stracił. Dziś piękność twą w całej ozdobie

Widzę i opisuję, bo tęsknię po tobie.

Lithuania, my country! You are health alone.

Your wealth can only ever be known by one

Who's lost you. Today I see and tell anew

Your lovely beauty, as I long after you.

Pan Tadeusz: The Last Foray in Lithuania, Adam Mickiewicz, translated by Bill Johnston, 2018

Meter

In fact, the most fundamental organizer of traditional English verse—and the most common such device worldwide—is not rhyme, but meter. In particular, English poets use a type of meter that counts units of stressed and unstressed syllables called "feet". Each line contains a number of feet, usually four or five for two-syllable feet and three or four for three-syllable feet.

Let's go back to Larkin and his earl. The lines are distinguished by an ABBCAC rhyme scheme, but we'll try using the meter to split them now. In red are the syllables I would stress in the first three stanzas:

Side by side, their faces blurred, the earl and countess lie in stone, their proper habits vaguely shown as jointed armour, stiffened pleat, and that faint hint of the absurd—the little dogs under their feet.

Such plainness of the pre-baroque hardly involves the eye, until it meets his left-hand gauntlet, still clasped empty in the other; and one sees, with a sharp tender shock, his hand withdrawn, holding her hand.

They would not think to lie so long. Such faithfulness in effigy was just a detail friends would see: a sculptor’s sweet commissioned grace thrown off in helping to prolong the Latin names around the base.

Is the meter perfect? No. It rarely is. But a general pattern of deploying feet of "one unstressed syllable-one stressed syllable," called an iamb (with some minor supplementary use of a "two unstressed syllables-one stressed syllables" foot called an anapest), is clearly visible. So is the fact that every fourth iamb ends on a word boundary:

(Side // by side, // their fa//ces blurred,) // (the earl // and coun//tess lie // in stone,) // (their pro//per ha//bits vague//ly shown) // (as join//ted ar//mour, stif//fened pleat,) // (and that // faint hint // of the // absurd) // (—the li//ttle dogs un//der their feet.)

(Such plain//ness of // the pre//-baroque) // (hardly // involves // the eye, // until) // (it meets // his left//-hand gaunt//let, still) // clasped emp//ty in // the o//ther; and) // (one sees, // with a sharp // tender shock,) // (his hand // withdrawn, // holding // her hand.)

(They would // not think // to lie // so long.) // (Such faith//fulness // in ef//figy) // (was just // a de//tail friends // would see:) // (a sculp//tor’s sweet // commi//ssioned grace) // (thrown off // in hel//ping to // prolong) // (the La//tin names // around // the base.)

And these four-iamb units are indeed the lines of iambic tetrameter that Larkin chose to write the poem in. An illustrative example of how meter organizes poetry.

Alliteration

See more on systematic alliteration

Alliteration refers to the repetition of sounds, especially initial consonants (e.g. with "s" and "sh" in "She sells seashells by the seashore"). Although alliteration is used quite commonly in both English prose and poetry, it is never systematic in the sense that, say, a rhyme scheme is systematic. This is not the case in all languages.

In the following Old Norse poem, the god Loki first announces his intention to bring strife among the gods who are feasting at the hall of the sea god Ægir; later, he accuses the goddess Gefjun of having slept with a boy simply for his necklace.

The poem is in a meter called ljóðaháttr. In ljóðaháttr, each stanza has four lines. The first and third lines are divisible into two halves, each half having two stressed syllables. The second and fourth lines have three stressed syllables. The meter demands a strict alliteration scheme that goes like this. In the first and third lines, the third stressed syllable must always alliterate with one of the earlier two stressed syllables, and the fourth syllable may optionally alliterate with the first two syllables, but cannot alliterate with the third. In the second and fourth lines, at least two of the three stressed syllables must alliterate.

These rules are as fundamental to ljóðaháttr just as much as the ABABCDCDEFEFGG rhyme scheme is fundamental to Shakespearian sonnets. This is another, and (for English speakers) much more exotic, way to organize poetry.

Bold are stressed syllables, red and orange the alliterating ones. For the purposes of Old Norse alliteration, all words that start with vowels or the consonant "j" (which is pronounced like "y" in "yellow", not as "j" in "judge") are considered alliterative.

Loki kvað:

"Inn skal ganga | Ægis hallir í

"Á þat sumbl at sjá;

"Jöll ok áfu | færi ek ása sonum,

"Ok blend ek þeim svá meini mjöð."

Loki kvað:

"Þegi þú, Gefjun! | Þess mun ek nú geta,

"Er þik glapði at geði;

"Sveinn inn hvíti, | er þér sigli gaf

"Ok þú lagðir lær yfir."

Loki spake:

"In shall I go | into Ægir's hall

"For the feast I fain would see;

"Bale and hatred | I bring to the gods,

"And their mead with venom I mix."

Loki spake:

"Be silent, Gefjun! | For now shall I say,

"Who led thee to evil life;

"The boy so fair | Gave a necklace bright

"And about him they leg was laid."

Lokasenna, translated by Henry A. Bellows, 1923

Parallelism

See more on systematic parallelism

Some poetic traditions, especially in Indonesia, Central America, the Ancient Near East, and among sign languages, organize poetry primarily through parallelisms. As with alliteration, English uses a lot of parallelisms too—but not systematically.

In the Biblical Hebrew poetic tradition, among the dominant organizers of the text is semantic parallelism. In semantic parallelism, a couplet (or sometimes triplet or more) of lines are placed in a pattern where the later line(s) usually serve(s) in the role of "focusing, specification, concretization, even what could be called dramatization" of the first line (Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Poetry, p. 19). In other cases, the couplets themselves are composed of largely synonymous lines (static parallelism), but the overall poem retains the structure of intensification and concretization. Many Hebrew poems are organized almost entirely into such couplet structures, as in the following work, the very first poem of the Book of Psalms.

We use a more recent translation that more accurately reproduces the parallelistic structures of the text:

ʾašrê hāʾîš:

ʾăšer lō hālaḵ baʾăṣaṯ rəšāʾîm,

ūḇəḏereḵ ḥaṭṭāʾîm lō ʾāmāḏ,

ūḇəmôšaḇ lêṣîm lō yāšāḇ.

Kî ʾim bəṯôraṯ YHWH ḥep̄ṣô,

ūḇəṯôrāṯô yehgeh yômām wālāyəlāh.

Wəhāyāh kəʾêṣ šāṯūl ʾal-palḡê māyim,

ʾăšer piryô yittên bəʾittô,

wəʾālêhū lō yibbôl—

Wəḵōl ʾăšer yaʾăśeh yaṣlîaḥ.

Lō ḵên hārəšāʾîm,

kî ʾim kammōṣ ʾăšer tiddəp̄ennū rūaḥ.

ʾal kên lō yāqumū rəšāʾîm bammišpāṭ,

wəḥaṭʾṭāîm baʾăḏaṯ ṣaddîqîm.

Kî yôḏêaʾ YHWH dereḵ ṣaddîqîm,

wəḏereḵ rəšāʾîm tōḇêḏ.

Happy the man:

who has not walked in the wicked's counsel,

nor in the way of offenders has stood,

nor in the session of scoffers has sat.

But the Lord's teaching is his desire,

and his teaching he murmurs day and night.

And he shall be like a tree planted by streams of water,

that bears its fruit in its season,

and its leaf does not wither—

And in all that he does he prospers.

Not so the wicked,

but like chaff that the wind drives away.

Therefore the wicked will not stand up in judgement,

nor offenders in the band of the righteous.

For the Lord embraces the way of the righteous,

and the way of the wicked is lost.

The Book of Psalms: A Translation with Commentary, Robert Alter, 2007

The parallelism that organizes the poem, both static and intensifying, is palpable. From stanza to stanza:

- Stanza 1 : The righteous man is introduced through three parallelisms of the structure "has not Xed in the Y". There are elements of both static parallelism—"the wicked's counsel", "the way of offenders", and "the session of scoffers" are largely synonymous—and parallelism of a progressive, intensifying sort; the wrongdoer against whom the happy man is defined is someone who at first "walks" with the wicked, then "stands" with them, and ultimately "sits" with them.

- Stanza 2 : The righteous man's behavior is elaborated on through two parallel statements sharing the subject "teaching" (bəṯôraṯ). The first line is a generalization—the man desires God's teaching—and the second line makes it concrete—the man's desire is such that he is always "murmuring" (or "meditating upon"; the verb yehgeh is ambiguous) God's teachings. The phonological similarity between YHWH "the Lord" and yehgeh "murmur/meditate", both of which follow the word bəṯôraṯ, stresses the parallelism.

- Stanza 3 : The first line compares the righteous man to a tree. The second and third lines display a static parallelism (both portraying the vitality of the tree) that intensifies the meaning of the first line. The fourth line completes the thought by explaining what the ultimate meaning of the tree simile is. In the original Hebrew, the fourth line also shows a degree of phonetic parallelism with the first line: wəhāyāh "he is" and yaṣlîaḥ "he prospers".

- Stanza 4 : The second line intensifies the first line's mention of the "wicked man" by offering visual imagery of what such a man would be like: "chaff that the wind drives away".

- Stanza 5 : The two lines share the parallel structure "the X will not stand up in Y", but the first line's verb yāqumū "will stand up" elliptically replaces the second line's verb. The wrongdoers are defined through two parallel synonyms, "the wicked" and "the offenders", while the places where they cannot stand are intensified in the second line; the "judgment" described in the first line is elaborated as the judgment of "the band of the righteous."

- Stanza 6 : The two lines are parallel in their opposition; they are also chiasmic, meaning that their parallelism is of an ABBA structure. The first line begins with the fate of a certain group ("the Lord embraces" them), then clarifies that this group is "the way of the righteous". The second line turns this around and begins by mentioning the "way of the wicked", and concludes both the parallelism and the poem with the fate of this group: it "is lost."

What our definition of poetry entails

The definition the Atlas uses for poetry is quite broader than what we're normally used to, in many cases, moreso than a given culture's definition of poetry.

For example, most English song lyrics are poetry; they're organized into non-syntactic, non-prosodic units through rhyme and meter. This goes against the usual English definition of poetry, which tends to be that a poem is a written or recited work, not something sung.

Or take the case of the Quran, the holy book of Islam. Many parts of the Quran are in rhyme. Yet the Quran explicitly says that the work does not constitute shiʿr, a word usually translated as "poetry", because it does not abide by the strict rules of meter that the Arabic language demands from a shiʿr. Instead, the Quran is defined as sajʾ, an Arabic word usually translated as "rhymed prose". However, by our definition, rhymed prose is also a form of poetry and the Quran a poetic work, albeit one with few restrictions on format. Our definition of poetry is broader than the range of works denoted by the Arabic shiʿr, just as it is broader than the usual English meaning of "poetry".

Completely meterless prose poetry, on the other hand, is unlikely to be treated as poetry by our definition.

The reason this definition is used over "poetry is what the culture defines as poetry" are twofold:

- Many cultures lack a specific concept of poetry. To use culture-specific definitions of poetry would mean that huge swathes of the globe are not covered.

- Even in cultures that do have a concept similar to the Western one of "poetry", there is a strong tendency to treat only the hyperformalized, rule-ridden literature of a tiny elite as poetry and ignore folk traditions. This did not seem quite fair.