Organizing methods: Meter / Alliteration and rhyme / Parallelism

Introduction

Until it was supplanted by Turkic languages in the tenth century, Tocharian was the easternmost of all Indo-European languages. Its speakers, the Tocharians, dwelled in the oasis cities of the Tarim Basin, linking East and West together in the great web of commerce now called the Silk Road.

Though the rise of the Arabs and the eclipse of Indian Buddhism would later make Central Asian trade a prerogative of Islam, Buddhism was initially a Silk Road religion. The Tocharians soon converted to the Dharma and began writing in an Indian-derived alphabet. Because of the extremely dry climate of the Tarim Basin, several thousand of their manuscripts have survived intact; the topics they cover range from the tedium of everyday life to the intricacies of Buddhist theology.

This surviving literature includes a number of poems, although all but a single love poem (reproduced below) are, in one way or another, about the Buddhist religion. The Tocharians appear to have had a thriving tradition of poetic scholarship of which only fragments survive. This was no doubt at least partly influenced by the poetry of the Indians from whom they learned to write, and in terms of content, Tocharian poetry veers closely to Indian archetypes. However, what survives of the methods of Tocharian poetry is extremely different from Sanskrit, and the extent of Indian influence on Tocharian verse remains actively debated.

Tocharian really consists of two related languages: Tocharian A and Tocharian B, the latter much better-attested. The two languages were already very different by the time of the first surviving Tocharian writings, by which point Tocharian A may already have been extinct as a language of daily use. Not much Tocharian A poetry survives, and the following discussion draws primarily on B (hence why this page is xtb.html, not xto.html).

Organizing methods

Meter

Tocharian poetry is governed by a syllable-stress meter like that of English, although Tocharian, unlike English, gives precedence to total syllable count over the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables. Tocharian meter works based on the following principles, which (unlike in English) apply to the entire stanza, not a single line:

These are strict rules. Then there are less strict ones:

The most common meter in Tocharian poetry demands four fourteen-syllable-line stanzas, divided into two seven-syllable units and four subunits of three and four syllables. The following would be the ideal pattern of stressed (S) and unstressed (U) syllables, with units and subunits marked:

S U S U | U S U || S U S U | U S U

S U S U | U S U || S U S U | U S U

S U S U | U S U || S U S U | U S U

S U S U | U S U || S U S U | U S U

But the following would also be permitted, if considered less elegant:

U S U U | S U U || U S U U | S U U

U S U U | S U U || U S U U | S U U

U S U U | S U U || U S U U | S U U

U S U U | S U U || U S U U | S U U

But a mix of the two is verboten.

Pinault 2008 identifies seventeen "principal" types of meter. No. 6 (4x14) was the most popular, and No. 4 (4x12), No. 9 (4x18) and No. 10 (4x25) were also common. No. 11, 12, 13, and 14 were all rare, with No. 14 being attested exactly once.

The following is a typical example of meter No. 9, written by a sinner who repents and begs the Buddha for forgiveness. Stressed syllables are bolded. The translation is mine, mostly from Pinault 2008's French, but with Adams 2013's English also consulted.

Mā ṣṣe nta kca cmelane ñem ra klyaussi kälpāwa, twār ṣpostaññe

Krent käṣṣintsa meṅkitse yolaiñesa mā ṣṣe nta aṣkār śmāwa.

Kwīpe-onmiṣṣem pwārasa tsaksau śmoññai śaulaṣṣai mā ṣprutkaṣä-ñ.

Ciṣṣe saimäś kloyomar. Nauyto-ñ yāmor, kāntoytär-ñ, kṣānti tākoy-ñ.

Not once in my births did I ever hear a name as thine;

Lacking a good teacher, I never stood back from evil.

In the flames of shame and remorse I burn the basis of life—it shall block me no more.

I fall to the refuge of thy realm. May my deed vanish; may it be rubbed off of me; may I find forgiveness.

Poem from H.149.26/30

Now, let's look at the meter here.

Out of the twenty units, all of them follow the "unstressed syllable at end of (sub)unit" rule, and the one exception, Mā ṣṣe nta kca, might look like one only on paper; Tocharian readers are often assumed to have stressed syllables they normally wouldn't if the meter demanded it. Nineteen follow the "one of the two syllables behind final syllable stressed" rule, and eight out of twelve four-syllable units are (S U S U).

Tocharian poets were capable of toying with meter quite ingeniously. More than a thousand years ago, an unknown worshipper scribbled the following enigmatic poem on the walls of a now long-abandoned Buddhist shrine:

Salpeṃ piś-cmela añiyātṣe puwarsa

Koyn kakāyāṣ po kapāntaṣṣi kāri po

Tāṣtär pelaikne śaulanmasa käryau se

Tneka preksau-me kā snai meṃtsi kläṃtsañcer?

Those of the five births burn in the fire of inconstancy

All having opened their mouths, all are pits of greed

He establishes the law and bought it with lives

Here indeed I ask you, "How do you sleep without a care?"

Poem from G-Su-1

This poem is in the (5 || 4 | 3) variant of Meter No. 4. Let's look at it just a bit longer.

Notice anything? Lines 1 and 2, and lines 3 and 4, have the same meter in the first and third units. But lines 2 and 3 have the same meter in the second unit, and so do lines 1 and 4 with only a minor difference in the very first syllable (which, again, might exist only on paper). The result is a meter scheme akin to a rhyme scheme, an interlocking web of meters; the meter of line 1 parallels both lines 2 and 4, the meter of line 2 both lines 1 and 3...

Alliteration and rhyme

Its irritable lack of a real title aside, G-Su-1 has a lot more going for it than its meter alone. Tocharians preferred alliteration to rhyme, and G-Su-1 is an excellent example of it.

First, the final stressed syllables of each line's two units alliterate, or at least sound similar. Line 2 goes even further with its alliteration in /k/. This is horizontal alliteration.

There is also vertical alliteration. The final word in each line's five-syllable unit starts with /p/, as does the final word of lines 1 and 2. The first word of the three-syllable subunit begins with /k/ in lines 2, 3, and 4; /k/ also heads the four-syllable subunit of lines 2 and 4. Finally, lines 3 and 4 begin with /t/. So there is an alliterative web as well as a metrical one:

Salpeṃ piś-cmela || añiyātṣe | puwarsa

Koyn kakāyāṣ po || kapāntaṣṣi | kāri po

Tāṣtär pelaikne || śaulanmasa | käryau se

Tneka preksau-me || kā snai meṃtsi | kläṃtsañcer?

Those of the five births burn in the fire of inconstancy

All having opened their mouths, all are pits of greed

He establishes the law and bought it with lives

Here indeed I ask you, "How do you sleep without a care?"

Alliteration may be yet more complex. Below, the two surviving fragments of the only non-religious Tocharian poem, the later half of stanza 2 and the first three-fourths of stanza 3 in what was probably a four-stanza poem. The reconstruction is Adams's; the translation, again, consults both Adams and Pinault.

II.

Mā ñi cisa noṣ śomo ñem wnolme lāre tāka mā ra postaṃ cisa lāre mäsketär-ñ.

Ciṣṣe laraumñe ciṣṣe ārtañye pelke kalttarr śolämpa ṣṣe mā te stālle śol-wärñai.

III.

Taiysu pälskanoym sanai ṣaryompa śāyau karttse-śaulu-wärñai snai tserekwa snai nāte.

Yāmor-ñīkte ṣe cau ñi palskāne śarsa tusa ysaly ersate ciṣy araś ñi sälkāte,

Wāya ci lauke tsyāra ñiś wetke klyautka-ñ pāke po läklentas ciṣe tsārwo, sampāte.

II.

Heretofore there was no human being dearer to me than thee; likewise hereafter there will be no one dearer to me than thee.

Love for thee, affection for thee—breath of all that is life—and they shall not come to an end so long as there lasts life.

III.

Thus did I always think: "I will live well, the whole of my life, with one lover: no force, no deceit."

The god Karma alone knew this thought of mine; so he provoked quarrel; he ripped out my heart from thee;

He led thee afar; tore me apart; made me partake in all sorrows and took away the consolation thou wast.

Poem from B-496

The first thing we recognize in Adams's reconstruction is an -āte end rhyme in stanza 3, something somewhat atypical for Tocharian poetry; rhymes were much less common than alliteration. Less conspicuous is the elaborate alliteration scheme. Tocharian has six sibilant sounds, [s] /s/ (the English "s"), [ṣ] /ʃ/ (the English "sh"), [ś] /ɕ/, [ts] /ts/ (the English "ts"), [tsy] /tsj/, and [c] /tɕ/.

In stanza 3, we find that:

Taiysu pälskanoym || sanai ṣaryompa || śāyau karttse- | śaulu-wärñai || snai tserekwa | snai nāte.

Yāmor-ñīkte ṣe || cau ñi palskāne || śarsa tusa | ysaly ersate || ciṣy araś ñi | sälkāte,

Wāya ci lauke || tsyāra ñiś wetke || klyautka-ñ pāke | po läklentas || ciṣe tsārwo, | sampāte.

|| s ṣ || ś || s ts s

|| c s || ś || c ṣ ś s

|| tsy ś || || c ṣ ts s

Parallelism

Tocharian poetry features repetition fairly frequently. In the poem below, one of the few whose authors bothered to sign their work, we have each line falling on the same word or morpheme, prāskau "I fear" and -ne "in" (Avīci is a Buddhist hell reserved for the worst of sinners, such as those who murder their own parents, where sinners burn in hellfire for 3.4 billion billion years):

Arai srukalyñe! Cisa nta kca mā prāskau,

Pontas srukelle; kā ñiś ṣeske tañ prāskau?

S-arai ñi palsko: cisa prāskau pon prekenne

Twe ṅke kalatar-ñ Apiś wärñai nreyentane

O death! Absolutely none but you I fear;

But all must die; should I alone have fear?

Such, alas, my thought: I fear you every moment

You, you will bring me to Avīci... to the hells

Poem from B-298, "the writing of the monk Dharmacandra"

Parallelism can be more intricate. In the following Tocharian A poem, each line repeats a declension of the noun tsraṣi "strong person" either at the beginning or end of each unit (the first line the plural genitive tsraṣiśśi "of the strong ones", the second line the plural allative tsraṣisac "toward the strong ones", the third line has both the plural nominative tsraṣiñ "the strong ones [subject]" and the plural genitive, and the final line the abstract noun tsraṣṣune "strength".) The final line lacks this parallelism, signalling that this stanza is at a close (revised from Adams's translation):

Tsraṣiśśi māk niṣpalntu || tsraṣiśśi māk śkaṃ ṣñaṣṣeñ;

Nämseñc yäsluṣ tsraṣisac || kumseñc yärkant tsraṣisac;

Tsraṣiñ waste wrasaśśi || tsraṣiśśi mā praski naṣ;

Tämyo kāsu tsraṣṣune || pkaṃ pruccamo ñi pälskaṃ.

The strong's riches are great, the strong's retainers many;

Foes bow toward the strong, honors come toward the strong;

The strong protect creatures, the strong's fears are none;

Therefore strength is good, the best of all, I think.

Poem from A-1a2/4

This is not the limit of the genius of Tocharian parallelism. The following line consists only of six words, four adjectives and two nouns:

Mäkceu ykeṣṣa kektseñe || tāu kenaṣṣe satāṣlñe

Wherever the body—exhalation there on earth

Poem from B-41a3

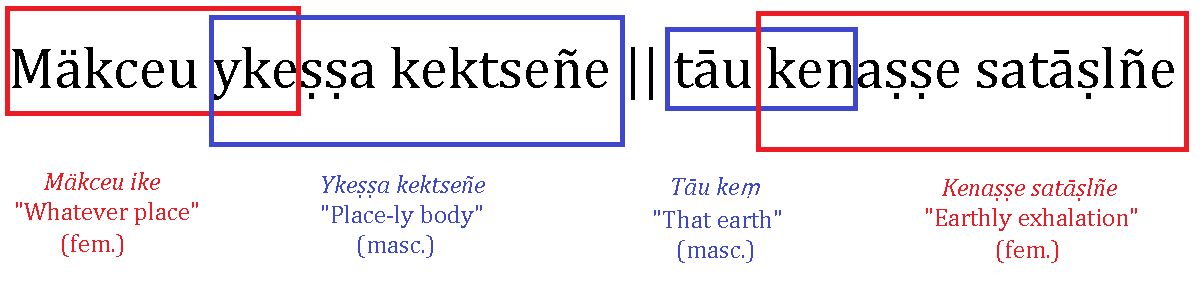

Translated word-by-word, the poem makes very little sense. Tocharian adjectives accord to either the masculine or feminine gender of nouns, which I mark below with red for feminine and blue for masculine. "Place-ly" is my attempt to translate ykeṣṣa, the adjectival form of ike "place":

Mäkceu ykeṣṣa kektseñe || tāu kenaṣṣe satāṣlñe

Whatever place-ly body || that earthly exhalation

First, note the careful balance in the genders and parts of speech of the six words: (M F F || F F M), (Adjective Adjective Noun || Adjective Adjective Noun).

The brilliance of the poem rests on the fact that the second adjectives of both units, ykeṣṣa and kenaṣṣe, are both formed with the adjectival suffix -aṣṣa/e as applied to nouns: ykeṣṣa from the feminine noun ike "place", kenaṣṣe from the masculine keṃ "earth". But here's the twist. Though built on a feminine noun, ykeṣṣa is the masculine form of the adjective; kenaṣṣe is feminine.

The result is that the poet has, out of six words, made four noun phrases:

Bibliography